Martina Kanneh has always had one passion: “For me, it has always been about helping people,” she says.

Today, Martina sits on the porch of the Well Baby Clinic in Buchanan, Liberia, wearing a motorbike riding suit. Her bike is parked nearby, and her helmet and backpack hang from the seat. The bag holds valuable supplies: medicines she will carry to community health workers in remote Grand Bassa County.

Martina is a community health supervisor, a role she has held for almost five years—and one she sought out due to her passion for helping others. “After university, I was working in a hospital setting, and then I heard about the community health program from a friend,” she says. “I have always loved teaching people and providing help and comfort. I thought, ‘This is something I must do—being a mentor.’”

She was excited about the opportunity to work in a rural health facility, where she would spend her days traveling to hard-to-reach areas to supervise community health workers. Liberia’s community health supervisors identify gaps in competency and quality of care and address them through mentorship and coaching. They review reports, service delivery records, and supply chain data, and restock community health workers’ supplies. As a registered nurse with a university degree, Martina had the right education for the role, as well as relevant experience. But one more qualification was included in the job description: Ability to drive a motorbike preferred.

In Liberia, very few women in Liberia hold motorcycle licenses, and driving is typically considered a man’s job. “When I saw the requirement, I said, ‘Wait, I don’t even know how to drive,’” she remembers. “But then I said to myself, ‘Martina, you can do it! You will do it!’ This was a big motivation for me, because here every man can ride a motorbike—and women can also do it! So when they asked me in the interview, ‘Can you drive a motorbike?,’ I told them I had no idea how—but I was very willing and able to learn.”

Martina was hired, and her work began with motorbike training provided by Last Mile Health. “It wasn’t easy in the beginning,” she recalls, laughing. “The training was only for a week, so it was intense. The second day I was able to move the bike on my own, and by the end of the week I was ready.”

She took on her new role with energy and care. “I supervise eight community health workers, each in their own catchment area,” she says. “In their daily work, they identify and treat sick patients. I make sure they are developing and using their skills properly, so when they treat someone, I will listen to make sure they are following the right treatment. I also ensure they are doing follow-up to check that the patients are completing the treatment and getting better.”

She sees her work as a partnership, with both community health worker and supervisor working together to deliver quality care. “If there are areas where the community health workers have challenges, we go through those topics together so I can coach and mentor them to help them to improve their understanding. Also, we talk through any challenges in the community and work through them to make sure the best care is given to our community people.”

Distance, Martina explains, is the biggest challenge. “Most of the community health workers are living very far away, and the roads are bad—there are always difficulties,” she explains. The skills she learned in her motorbike training have equipped her to close the distance. “Riding a motorbike is very important for this job because most of our communities cannot be reached by road, only small paths. There is no car route. Many communities are at least four hours’ walk, so it would take me all day to walk there and back. But trust me, with the motorbike it is much easier: I can take my bike, go into the community, and come back.”

Martina’s motorbike equips her to bridge the distance between remote communities and health services.

For patients, distance often remains a barrier. “Our common challenge is with referring women for antenatal care. When it’s far to the facility, sometimes people will look at the distance, and they won’t go,” she says. “So I talk to my community health workers, and when they have someone they are referring, I will go, and we will talk together about the importance of going to the health facility—and the dangers of staying in the community without receiving care if they are pregnant.”

She vividly recalls a time when distance nearly cost a patient her life. “One time I was on the way to the health facility and I got a call from one of my community health workers saying that a woman in the community had preeclampsia and had gone into shock,” she remembers. “I quickly rushed there, and together we talked to her family and we were able to refer her and get her to a facility, where she had surgery and a successful delivery. Presently, she tells other women, ‘We are alive because my doctor had me go to the facility.’ This has made us so proud, because we can really see the impact the program has made.”

Martina finds purpose in helping community health workers change patients’ lives—but her job as a supervisor has changed her life, too. “This is my first paid work. My work in the hospital was without pay,” she explains. “My salary as a community health supervisor is what keeps my family up. I am a single mother, and I am sending my two kids to school because of the pay I earn.”

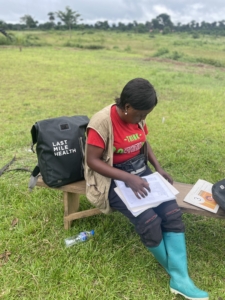

Martina reviews community health worker training materials and patient workers while conducting supervision.

Salaries for supervisors and community health workers are essential, Martina says: a paid, professional community health workforce makes quality primary care possible even in remote areas. “The National Community Health Program is very important for Liberia because we have rural areas where there is no health facility. This program helps reach people in hard-to-reach areas and help people live a healthy life. That is our goal.”

She emphasizes the crucial need for ongoing funding. “Our communities need this program to keep going, and what will keep it going is having drugs fully stocked, because without them, there can be no care. And we need to continue to train up our community health workers to the level we want them to reach. We must give them their salaries and supplies. If we are not supported, we are not working.”

Equipped with lifesaving medicine, Martina sets out each day on her motorbike. Together, she and the community health workers she supervises bridge the distance that would otherwise be a barrier to care. And Martina is dismantling gender-based barriers, too: across the communities where she works, girls recognize her when they see her appear on the narrow path, riding her motorbike and carrying medicine. For many of them, she serves as a role model, inspiring them to work toward a future like hers. “Aunty Martina can ride,” they say. “So someday, I can ride too.”