Across the globe, health workers have been unable to deliver antimalarial commodities and services due to lockdowns and social distancing enforcement; vaccination campaigns for polio, measles, cholera, HPV, yellow fever, and meningitis have been postponed; and about 80% of tuberculosis, H.I.V. and malaria programs worldwide have reported disruptions in services, with one in four people living with H.I.V. reporting problems with gaining access to medications. When health systems are overwhelmed during outbreaks, deaths caused by lapses in routine care increase dramatically. With visits for preventative care drastically decreasing, COVID-19 threatens to reverse decades of progress and cause over 1.2 million deaths in low and middle income countries due to disruptions to health services.

In Liberia alone, this could mean an additional 10,000 lives lost.

Well before the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Liberia in March, the government began taking swift, evidence-based measures to control the virus. These measures have thus far included running mass community awareness campaigns; rapidly mobilizing contact tracing, active case-finding, and infectious disease surveillance systems across the country; enforcing risk mitigating measures including curfews, travel restrictions, and mandated public mask use; distributing personal protective equipment to health facilities; and providing refresher training to community and frontline health workers on infection prevention and control practices to mitigate spread in community and healthcare settings. Though significant attention has been directed towards preventing, detecting, and controlling the spread of the virus, vulnerabilities in access to routine healthcare still remain.

During crises like COVID-19, essential health services are often interrupted—which can be deadlier than the virus itself. As Liberia continues to see a steady increase in COVID-19 reported cases and deaths, community and frontline health workers will be critical in mitigating the risk of disruptions to primary healthcare that might result from restrictions on movement, staff and supply shortages, and health worker and patient fears of contracting the virus.

With 60% of Liberia’s population living 5 km from the nearest health facility, an already arduous journey to seek medical care—whether routine or emergency—has been made even more complicated by COVID-19.

“Public transportation, which many Liberians rely on to visit a health facility, has seen a dramatic spike in fares to make up for the reduction in passengers and making it difficult for some people to get to the hospital” explains Koffa Tenbroh, a County Supply Chain Specialist for Last Mile Health in Rivercess County, Liberia. “This is why community health workers who live in the communities they serve are important and can help identify and support sick people.”

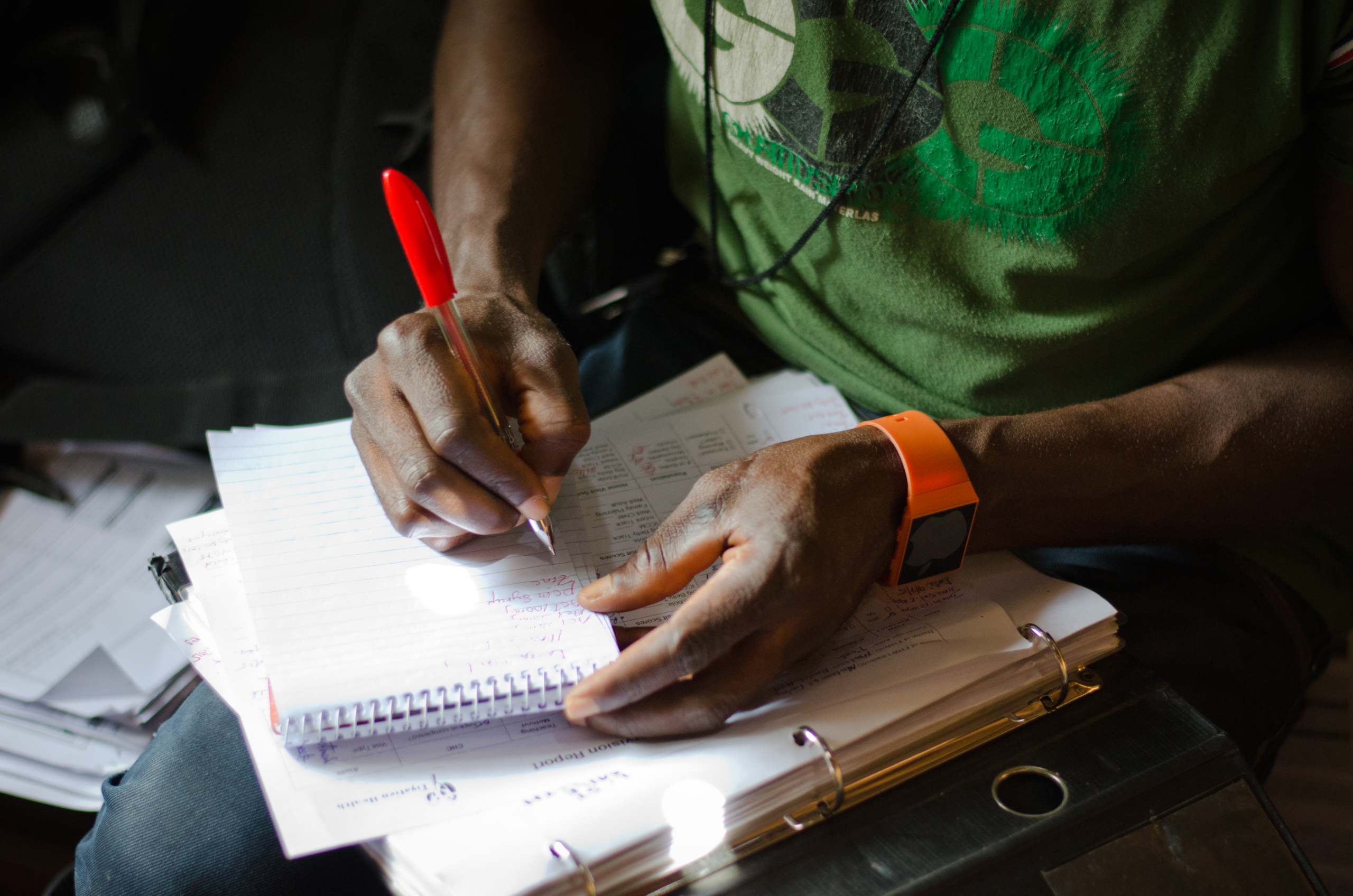

Teams of community and frontline health workers are working diligently to ensure patients can access care when and where they need it. Though global disruptions have made the health supply chain challenging, Last Mile Health and its partners including the Liberia Ministry of Health continue to equip community and frontline health workers with vital medication, tools, and supplies so that they can maintain essential health services.

“Generally, access to healthcare includes access to a health facility, a health worker, and treatment or medicines. Restrictions and panic related to COVID-19 have disrupted the supply of essential drugs across the globe,” explains Koffa. “This could significantly impact services that rely on the stock of commodities. For example, for HIV and tuberculosis patients, drug adherence is critical for staying healthy and if patients can’t get the medicines they need it may be difficult to keep their virus under control.”

Essential personal protective equipment for community and frontline health workers to continue providing care.

In addition to facing a potential shortage of essential medicines and supplies, an initial lack of adequate personal protective equipment had community and frontline health workers concerned about the safety of themselves and their communities.

“People are still carrying the feeling of the Ebola virus, so hearing about the coronavirus has actually put a lot of stress on the healthcare delivery system,” explains Sahr Joseph Nyuma, Last Mile Health’s Rivercess County Manager. “We realized that essential services at the hospital were not being [utilized at normal levels]. Patients were not coming to the health facility because they had fear that they would be infected. We also had issues [with availability of personal protective equipment]. And worst of all, we had serious knowledge gaps in terms of what health workers need to do to prevent and manage the spread of coronavirus disease.”

But with support from the Ministry of Health and Last Mile Health, the Rivercess County Health team has trained all health facility staff—including clinicians and non-clinical staff like pharmaceutical dispensary staff and hospital cleaners—in infection prevention and control and provided personal protective equipment to enable them to “keep safe, keep serving.” Last Mile Health also collaborated to train all community health workers to educate their communities on the signs and symptoms of COVID-19, dispel myths linking COVID-19 to Ebola, encourage community-based risk mitigation measures like social distancing, hand washing, and mask use, and refer any suspected cases for treatment.

“[When we had our first suspected case in the county,] our health workers became very afraid… [because they hadn’t been trained on COVID-19 yet and] they weren’t confident that at that point in time they could provide care to this patient who was suspected of having COVID-19,” explains Sahr. “Now they are very confident that there are screening measures that have been put in place to assess patients… and all health workers are now confident that they have the skills to screen for this condition and the actions they need to take [if there is a suspected case].”

Though the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 are complex and, mostly still unknown, measures to combat the spread of the virus across the country are taking into account the competing factors that threaten the delivery of lifesaving health services. Koffa, Sahr, and their colleagues are working to build the confidence of both patients and the health workforce.

While everyone is vulnerable to getting sick, the current pandemic has shown that too often the most vulnerable populations can’t get healthcare when they need it, reinforcing the urgent need for universal healthcare—and the critical role teams of community and frontline health workers play in achieving it.