Peter Zeo

‘’Community health workers are important because we go to the most remote parts of the village where there is no access to health facilities or where an ambulance cannot reach. Community health workers are the go-to people,’’ says Peter Zeo, a community health worker in Liberia’s remote Rivercess County.

Before Peter was recruited as part of the National Community Health Assistant Program, residents of Nyanee District had only one way to reach the nearest health facility: walk for 20 minutes on a rocky path through the forest to get to the Cestos river, then pay for a ferry or canoe to take them to the other side. Tragically, the distance and cost were an obstacle for many families, meaning they could not access the timely care they deserved. “Every three months, children died from malaria,” Peter shares.

Peter was born and raised in Nyanee District One, and his motivation to serve his community stems from his deep roots in the area, which represent his family’s past, his current life, and his children’s future. “I was motivated to become a community health worker because I wanted my people to see there’s hope despite the fact that we don’t have a health facility,” he says. “Our children can live and not die from malaria and other treatable illnesses.’’

In May 2000, Peter became a community health volunteer, working as a polio vaccinator with the Rivercess County Health Team. “When I volunteered for the Rivercess County Health Team during the polio vaccinations, I realized that it would be great if we could have someone as a nurse or doctor here in my community, on the other side of the river,” he says. “Because of the distance to the hospital and the lack of money, my people were using country herbs when they got sick.”

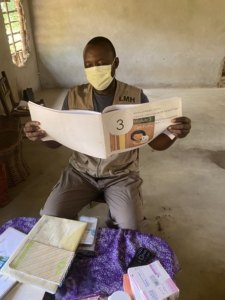

Peter Zeo prepares to conduct routine visits in his community in Rivercess County, Liberia.

Peter was fully trained as a professionalized community health worker, known locally as a community health assistant, in 2016, when the National Community Health Assistant Program was launched. This program aims to deploy one community health worker to every rural and remote community in the country to bridge the distance between patients and the health facility. Peter was trained to deliver primary health services to his neighbors, like diagnosing and treating malaria, identifying malnutrition in children, and providing prenatal care to pregnant women. He also works closely with his supervisor, a trained nurse, to ensure he is delivering quality care and can coordinate referrals to the health facility for advanced cases. Importantly, he is also paid for his work, which allows him to support his family of eight. Peter says, “When Last Mile Health arrived, I was happy to be able to help my people and my community.”

Now, Peter makes routine visits and follow-ups on a regular basis. Today, he says there are fewer reports of children dying from treatable illnesses and the community has grown to trust him, with children with colds running up to him to say, “Dr. Man, I’m coughing.”

Peter was able to sustain his work during the COVID-19 pandemic. He is fully vaccinated against COVID-19, and has encouraged the majority of his neighbors to do the same. He’s pleased that, as a result of his efforts to raise awareness about the virus, members of the community started washing their hands, wearing masks, and maintaining social distance.

“The most rewarding aspect of my job is that I can help my community without a college degree or money, and my community’s regard for me as a community health worker exceeds anything I could have imagined,” Peter states. “The children in my community are healthy and able to pursue their dreams of going to school and becoming somebody in the future.”

Looking to his own future, Peter hopes to one day become a community health worker supervisor so he can support another member of his community to do this life-saving work. In addition, he hopes partners like Last Mile Health will continue to work with the Ministry of Health to scale the National Community Health Assistant Program. “We don’t want our children to die from malaria and other treatable illnesses simply because they can’t afford it and we don’t have access to a health facility,” he says.