When she was a child in rural Ethiopia, Workinesh Getachew had an experience that would change her life.

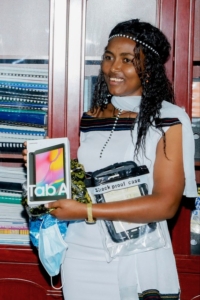

Workinesh Getachew

“One day, I was called inside my neighbor’s house with my friend. We witnessed a delivery,” Workinesh recalls. Without medical training or the support available at a health facility, the traditional birth attendant relied on neighbors to assist–and when the birth became complicated, the trauma the mother experienced would stay with Workinesh forever. “It is hard for me to speak of even now,” she says, closing her eyes and turning away. “Everything was wrong, and horrific for a woman like me to imagine going through in life.”

From time to time, health workers visited Workinesh’s community in Ethiopia’s East Shewa zone to evaluate the sick and provide care, free of charge. They gave Workinesh a goal: to become a community health worker. “The care they give, the acceptance among the community has been a continuous motivation for me,” she says.

Now 22 years old, Workinesh has worked as a community health worker, known locally as a health extension worker, for almost five years. After completing her training through Ethiopia’s national program, Workinesh was placed in a different community from the one where she grew up. “Even if I don’t work in the community I was born in and raised in, this community has accepted me as a family,” she says. “There is no water here. They travel seven hours from home to where they get water and back. They even share water with you, something they spend more than half of their day searching for.”

But when Workinesh first arrived, she faced daunting challenges. The health post serving her catchment area was in disrepair. “You could see through the holes it has on the walls inside and out,” she remembers. “As I looked at the surroundings, I cried, thinking, ‘How can I live and work here?’”

Workinesh Getachew laying blocks during the renovation of the health post.

Still, Workinesh had a job to do–a job she had felt called to do since she was a child. “As I started to know the community, I started to understand the challenges they are in,” she says. “I mobilized the community leaders, and they influenced the community members to collect money to rebuild the health post.”

As weeks turned to months, Workinesh began to feel at home. She adjusted to her new routine: three days a week she conducted home visits, and two days a week she worked from the health post. Her work focuses on four major areas: maternal and child health, hygiene and sanitation, communicable and non-communicable disease, and health education and promotion. On a day of home visits, she might provide malnutrition screenings, assist with a vaccination campaign, complete a post-natal care visit, and educate community members on better sanitation practices. At the health post, she might conduct an antenatal appointment for a pregnant woman, treat a tuberculosis patient with medication, and refer a patient with a severe illness to the health center for a higher level of care.

“Since I know how far they travel to reach here I don’t ask them to wait for me until I finish my lunch or say this is my break time,” she explains. “My clients are my priorities.” The people in her community have been generous and giving–and Workinesh has earned their trust with her willingness to go any distance to change health outcomes.

One such instance came when she noticed a rise in cases of diarrhea. “We saw there were no toilets in their houses, no community toilets,” she explains. “Due to the knowledge gap and the level of other challenges they face every day, using toilets is not even amongst the concerns.”

Workinesh knew proper hygiene and sanitation were the key to helping her community reduce cases of diarrhea–but how could she convince her neighbors to take on the burden of building toilet facilities in a community where simply accessing water requires a seven-hour walk?

“The environment is harsh, windy, and hot with a desert type of climate,” she says. “The farthest household from our health post is a two-hour one-way distance. Since there are no transportation methods we go on foot. And to see nothing has changed in our next three or four visits is disappointing. But after a while I stopped being disappointed and started to dig myself.”

Workinesh led the community youth in building toilets for those who couldn’t build for themselves, while a group of women she had educated–a “woman developmental army,” influential community members equipped to serve as a model of best health practices–built their own facilities and led the way for others. “We have decreased diarrheal cases now,” Workinesh reports. “If you ask [the people in my community], they will say, ‘Now we understand why she did all that.’”

It has been many years since Workinesh was a little girl watching a woman give birth without the support of a trained health worker or the safety of a clean facility, but her compassion remains the same. “My source of strength and satisfaction in this job is to see my community members happy,” she says. “I want to grow, be educated, and serve my community more than what I am doing now. I want to be a doctor.”

A facilitator leads the reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health blended learning training for community health workers.

For now, Workinesh works every day to improve life and health for her neighbors–and she is committed to keeping her skills sharp so she can provide them with the highest quality of care. Recently, Workinesh completed a blended refresher training on reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health designed by the Federal Ministry of Health and Last Mile Health–and she earned a perfect score. She has also committed to work as an advocate and ambassador for digital learning to empower health extension workers with digital learning resources to continuously improve their knowledge and skills.

“I urge the health workers and government officials in health to work on rural community health,” Workinesh says. “As a health worker myself I understand that the price a health worker pays while providing care is not estimated with what they earn. The satisfaction they get from helping others, the peaceful nights they spend sleeping, and the community love and blessing have more value.”