When reflecting on why he became a community health worker, Mark-Pay Kaiyuway’s answer is simple: “My community needed the medicines.”

Mark-Pay lives and works in Grand Bassa County, Liberia, providing primary care to roughly 300 people across five towns. Many of his neighbors are farmers, growing crops like bitter greens, cassava, and potato greens, and the area is remote. “Ceegaye Town is a five-hour walk to the nearest health clinic,” he explains. “People can take the other way around and take a motorbike, but it might cost 300 to 500 Liberian dollars.” Thanks to Mark-Pay, his neighbors no longer have to make this long and costly journey to get care for themselves and their children.

When Liberia’s flagship National Community Health Program first came to his community, he listened with interest. “I told my wife that I wanted other children to have the medicine they needed,” he recalls. While his own children were all over five years old already, he saw the needs of younger children in the community—and he wanted to ensure no child suffered or died from preventable, treatable illness.

He was selected as a community health worker (known locally as community health assistants) , and began training through the Ministry of Health and Last Mile Health. “I learned plenty of new things,” Mark-Pay remembers. From first aid, to diagnosing and treating childhood illnesses like malaria and diarrhea, to community education on topics like hygienic food and water use, to the importance of receiving routine childhood immunizations and the COVID-19 vaccine, his training covered a full package of primary health services.

Community members cross a footbridge in Grand Bassa County. Travel in this remote county creates challenges for those in need of care.

Today, Mark-Pay spends four hours each day conducting routine household visits across the community. He also provides health education on key topics like malaria prevention. “When the sun is going low, you have to start closing the windows,” he tells his neighbors. “Make sure there is no standing water around the house. Make sure children and pregnant women are sleeping under a mosquito net.” If a child has symptoms of malaria, he will give them a rapid diagnostic test. If the result is positive, he will provide medicine for malaria and monitor the child for the next few days, ensuring they don’t need advanced care at the facility.

At all hours, Mark-Pay is ready to respond to emergencies like a sick child or a woman facing pregnancy complications. “I learned to recognize danger signs in pregnancy and when to advise pregnant women they need to go to the clinic,” he says. “For example, last month I visited a pregnant woman named Teresa. She told me she had severe back pain, and I told her she needed to go to the clinic. There they found she had an infection. They gave her medicine, and now she is well.”

For his work, Mark-Pay receives a salary of $70 USD each month, which he uses to pay for his children’s schooling. He is proud to be providing new opportunities for his own children while improving the health of all children in the community. “People trust me now because they have gotten better or their children have gotten better after being treated by me,” he says.

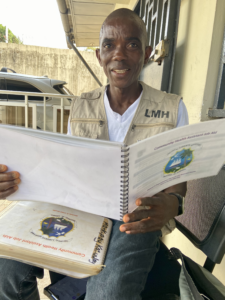

Mark-Pay with his supervisor, Pillar Nufepolu. Community health services supervisors like Pillar ensure community health assistants like Mark-Pay have consistent support to carry out their work.

Still, Mark-Pay faces many challenges. “The distance that we cover is very far,” he explains. Sometimes, when he arrives to conduct a routine visit, people aren’t home and he must search for them in the fields or wait for them to return. “Sometimes the visits become quite long this way and so I have to spend the night, either carrying food or paying for it,” he says.

At night, people sometimes come to Mark-Pay with emergencies. “Their child is sick, hot with fever,” he says. “I have no electricity at night, so sometimes I am trying to diagnose and treat a sick child using only the light of my phone.”

To provide the best care for his patients, Mark-Pay says, the national program needs strong financial support. “Community health assistants need to always have medicine available so people know they can rely on us,” he says. “We need materials like flashlights or lanterns for working at night and bicycles since the distances are sometimes very far.”

He knows the value of having a health worker within reach, for mothers like Teresa and for children like his own. It’s important to invest in community health, says Mark-Pay, “because community health workers are a trusted resource in their communities.” On a home visit or late at night, when his neighbors need care, they know they can find it through him. “People in the community need help and they already know us,” he says.