“Ceegaye Town is a five-hour walk to the nearest health clinic,” says community health worker Mark-Pay Kaiyuway, describing one of the five towns where he provides primary care services in Grand Bassa County, Liberia. “People can take a motorbike, but it might cost 300 to 500 Liberian dollars,” Mark-Pay explains—a price most families can’t afford. In rural and remote communities like those he serves, people count on community health workers for access to healthcare. “Community health workers need to always have medicine available so people know they can rely on us,” says Mark-Pay.

Most community health workers in Liberia operate in hard-to-reach areas, with long journeys from one patient to the next and limited access to the internet, cell networks, and electricity. Since the launch of Liberia’s national community health program in 2016, community health workers have transformed access to care, delivering over one million treatments for children under five. But they have had minimal opportunities to leverage technology as part of their daily work, like reporting data from patient visits or supply stock-outs. Reports are handwritten, a time-consuming task that introduces opportunities for errors and misplaced paperwork—and means community health workers have less time for patient visits.

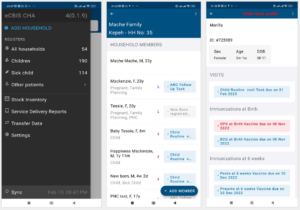

But that is changing, as Liberia’s Ministry of Health has launched an ambitious effort to create a digital information system that can connect community health workers at the last mile with every level of the health system. To develop and pilot the electronic Community-Based Information System (eCBIS), the Ministry of Health has partnered with technical experts, including Last Mile Health, Ona, UNICEF, and VillageReach. “eCBIS is a digital version of the existing and standardized national community health information systems,” explains Brian Ssenoga, Last Mile Health’s Director of Digital Health, Liberia. “It will harmonize data collection, workflow management, supervision, and supply chain into a single platform for community health workers and their supervisors to coordinate care, collect data, and make data-driven clinical decisions.”

Last Mile Health engaged with Liberian government bodies in Liberia to co-design and validate content for the eCBIS application, while Ona built the system from design to implementation using the OpenSRP2 platform. In September 2023, the Ministry and partners rolled out eCBIS in a pilot program. Equipped with smartphones, community health workers received training on the eCBIS app’s functionality and how to utilize it in patient care and reporting. Simultaneously, supervisors received training in the app’s supervisor-specific interface, preparing them to leverage data and provide stronger support. “The eCBIS pilot was tested across four different Liberian counties,” says Brian. In Liberia, community health workers receive training in a comprehensive package of essential primary care skills, and eCBIS will support them across all areas.

For community health workers, eCBIS will mean more efficient work, more reliable supplies, and more time to focus on the core of their work: providing care to patients. “eCBIS is unique because it’s designed to be implemented in extremely remote areas, and allows data to be collected and transferred via bluetooth and without internet access,” Brian says. “It is going to significantly impact Liberia’s community health worker program through improved decision support, a greater volume of care tasks completed, and timeliness of care provided in the community. eCBIS will also provide critical coverage, performance, and supervision metrics for community health workers and their supervisors.”

eCBIS will also transform health leaders’ work: it will give them access to more timely data, offering a snapshot of the health of the population as a whole and information on outbreaks and emerging disease threats. For the Ministry and partners, the pilot will provide key insights into the work ahead to achieve these aims. Next up: using data to refine eCBIS and leverage lessons learned in the system’s national scale-up. “Together with the Liberia Ministry of Health, Last Mile Health and partners will support iterations and adjustments to the application based on feedback from the pilot assessment and insightful feedback from users,” Brian explains. “The pilot will gather evidence and support continued use in the respective counties before being fully scaled across 4,000+ community health workers and their supervisors.”

For the Ministry of Health, the eCBIS represents an exciting step in modernizing its existing system and building its capacity. The Ministry-led initiative will go through additional decentralization and systems building with partnership from Last Mile Health and other partners. Ultimately, county health teams will fully manage the system—a key consideration in the piloting and roll-out of eCBIS. “We’ve been intentional in collaborating with country health teams in the field,” says Brian. “We want the Ministry of Health staff to have technical skill to be able to assess and review the app and the platform. We want them to own the platform.”

Akim Roberts, the Ministry of Health’s Monitoring and Evaluation Data Manager in Rivercess County, emphasizes the role of local Ministry staff in ensuring the roll-out is successful.“The app has a lot of value for our work, but we need to make sure we work closely with the county team so that we are fully involved in the implementation,” he says.

Overall, eCBIS targets a pervasive problem in health equity: a devastating lack of access to care in the world’s most hard-to-reach communities. Globally, two billion people lack access to essential care because they live in rural and remote communities outside the reach of the health system—and these are the same people who lack access to digital tools. “To achieve the potential of digital health innovations in public health systems, we must design solutions that put the last mile first,” says Last Mile Health CEO Lisha McCormick.

eCBIS, once nationally scaled, represents one such solution. “Without data, you have a very incomplete picture of the needs and the burden of disease in any given country,” Lisha says. “If you are not counted, you are invisible, and there is no finance or medicine or workers to meet your needs.”