For many community health workers in Sierra Leone, the drive to join the health workforce comes from a desire to help stop preventable illnesses and deaths in their communities. For Amadu Kamara, this drive is deeply personal. “I was motivated to become a community health worker because I lost three of my kids between 2005 and 2009,” he shares. “They died due to lack of knowledge in my community on what to do when a child is sick. Their illness was preventable and curable.”

Compelled to help ensure other families would not experience such devastating loss, Amadu entered training to become a community health worker in Kapairoh, his community in Sierra Leone’s Kambia District. “When I started in 2010, there was no payment incentive. I was just a volunteer for my community,” he explains. “But when I heard of this opportunity to be trained as a community health worker, I grabbed it and said to myself, ‘This will help me to learn more about what killed my children, and I will use this learning to save my other children and my community as a whole.’”

During Amadu’s long career, Sierra Leone’s community health worker program has evolved and strengthened, with the Ministry of Health adjusting its national policies to align with community needs and global best practices. In 2021, the Ministry integrated training so all community health workers would receive training across an essential package of primary healthcare topics, and Last Mile Health supported training and supervision on the new integrated curriculum. It was during this training that Amadu discovered an opportunity to increase his impact.

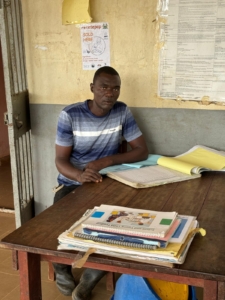

“In 2022, during training, I was chosen to be a peer supervisor due to my hard work and commitment,” says Amadu. In his new role, he councils other community health workers and assists at the Kambia District Health Management Team’s under-five clinic. “As a supervisor, I am supposed to visit all my community health workers at least once a month in their various communities,” he explains. “I spend time at the health facility to assist the staff and learn every day.”

To perform at their best, community health workers need the right support, including fair pay, strong training, reliable supplies, and regular supervision. Amadu and his team face challenges that can make work difficult to complete: “I am not able to work effectively as a peer supervisor because I don’t have transportation, so I am not able to visit them as frequently as I should,” he shares. Covering long distances to visit patients across large service areas also creates challenges for those he supervisors, Amadu adds. “A community health worker serving two or three communities may not be effective in all these communities, especially those that are hard to reach.”

A community health worker in Sierra Leone measures a child’s upper arm circumference to screen for malnutrition.

Sometimes, Amadu says, community health workers and supervisors must use their limited stipends to cover supplies they need for work. “Even though we now receive an incentive, it is not commensurate with the service we render to our community people,” he says. In Sierra Leone, peer supervisors receive the equivalent of $30 USD per month, while community health workers receive $15 in easy-to-reach areas and $25 in hard-to-reach areas. Although paid incentives are a step above the reality in many countries, where community health workers still work as unpaid volunteers, this compensation falls short of a living wage. For community health workers and their supervisors, the need for equitable pay is urgent.

Despite the challenges, Amadu’s dedication to his work has not wavered, and he is determined to do all he can to ensure people in his community—and the communities where he works as a supervisor—can access the care they need. He is committed to learning, growing, and providing mentorship so those he supervises can improve their skills and knowledge, too. “Since I started as a community health worker in 2010 until today, I have learned a lot of basic first aid and causes of death in under-five children,” he says. “As a supervisor, I have learned about mentorship and coaching. I can develop an action plan for community health workers I supervise and use it for follow-up and mentorship. I use my new skills to ensure that each person I supervise knows and understands where they need to improve on their work, and ensure that they work toward it on a good timeframe.”

Peer supervisors in Sierra Leone test a new tool designed to standardize and strengthen their supervision visits with community health workers.

He stresses the importance of regular supervision for community health workers: “It reminds them to work effectively, and it will help them be confident about their work,” he says. “It increases the performance of community health workers.”

A strong community health workforce means better care for patients, Amadu explains—especially in rural and remote areas. “Community health workers go to the farthest communities to save lives,” he says. “They bring awareness to the communities about health and tell them how to prevent diseases. An effective community health worker can help improve health outcomes, improve the health of children and pregnant and nursing women, and reduce maternal death and death in under-five children.”

Amadu has a message for partners and those who want to change the reality of healthcare access in remote communities. “As a community health supervisor, I’d like to inform them about the importance of community health workers,” he says. “Community health workers are the backbone of primary health care delivery, particularly in hard-to-reach areas. We promote preventive care and connect patients to the health facility. Let us continue our work and training. We are excited to learn more.”

Each day, Amadu will continue his work delivering care, supervising others, and speaking out for community health, driven by the knowledge that this work saves lives. “Since I became a community health worker, I have never lost any of my other children,” he shares. “Now I know that when a child is sick, the health facility is there to treat them.”